The Byzantine Emperors

2 posters

Page 1 of 1

The Byzantine Emperors

The Byzantine Emperors

This thread will put information about every Byzantine emperor from Zeno to Constantine XI Palaiologos. Each day information about the next emperor will be put into the thread. This will only include the emperors from the fall of the Western Roman Empire to the fall of Constantinople it will not include emperors from the Eastern Roman Empire.

I Like The Holocaust- Centurion

- Posts : 237

Join date : 2017-07-09

Re: The Byzantine Emperors

Re: The Byzantine Emperors

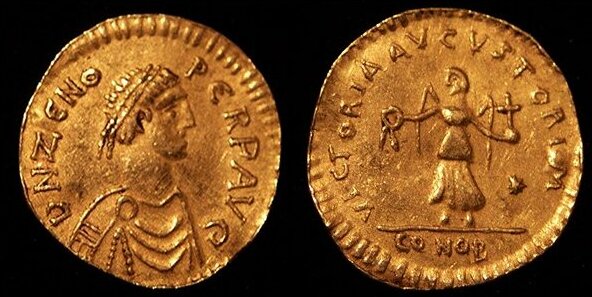

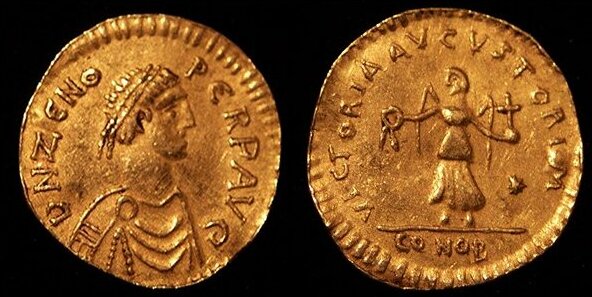

Zeno the Isaurian (425-491) Reigned (9 February 474 – 9 January 475

August 476 – 9 April 491)

Zeno's original name was Tarasis, and more accurately Tarasikodissa in his native Isaurian language. Tarasis was born in Isauria, at Rusumblada, later renamed Zenonopolis in Zeno's honour. His father was called Kodisa (as attested by his patronimic "Tarasicodissa"), his mother Lallis, his brother Longinus. Tarasis had a wife, Arcadia, whose name indicates a relationship with the Constantinopolitan aristocracy, and whose statue was erected near the Baths of Arcadius, along the steps that led to Topoi. The emperor Leo called him to Constantinople as the leader of a force of Isaurians in order to counter the ever-growing German influence over the empire. Also a special imperial guard was set up, made up entirely of Isaurians, and Zeno was granted command of this highly important force. In 466, he exposed the treachery of Ardabur, the son of the Alans eastern magister militum Aspar and made himself even more indispensable. By 468, when Leo's incompetent generals led the Byzantine fleet to disaster in a campaign against the Vandals, was considered Leo's best general. It was only at that stage that he assumed the name Zeno. Apparently it was the name of a dignitary of high standing back in Isauria, and Zeno thought it more befitting of his new high office to have a name less common than Tarasicodissa. To further increase the bond with his new Isaurian guardsmen, Leo married his elder daughter Aelia Ariadne to Zeno. Although designed by Leo to secure the Isaurian support against the aforementioned ambitious minister Aspar, this political arrangement brought them a son, who was a boy to became the emperor Leo II upon the death of his grandfather in 473. In AD 467-8 Zeno was given the powerful position of 'Master of Soldiers' in Thrace to repel an assault by the Huns under the son of Attila, Denzig. While on a campaign in Thrace he narrowly escaped assassination instigated by Aspar. On Tarasicodissa's return to the capital, Aspar was killed on Leo's orders and Tarasicodissa became magister militum in his own right. Next, in AD 473 Zeno was made 'Master of Soldiers' of the eastern empire, taking Aspar's place. In October AD 473 Leo elevated his five year-old grandson, who was the son of Zeno and Aelia Ariadne, to be co-emperor Leo II. When Leo became ill and died on November 17, Zeno became sole emperor. He continued to be unpopular with the people and senate because of his "foreign" origins. A revolt fomented by Verina in favour of her brother Basiliscus in January of 475 and the antipathy to his Isaurian soldiers and administrators in Constantinople forced him to flee the capital for the city of Antioch. Zeno was compelled to shut himself up in a fortress and spent the next 20 months raising an army, largely made up of fellow Isaurians, and marched on Constantinople in August 476. The growing misgovernment and unpopularity of Basiliscus ultimately enabled Zeno to re-enter Constantinople unopposed in 476 after an army led by the general Illus defected to Zeno. His rival was banished to Phrygia, where he soon afterwards died. Restored to rule of the entire empire, Zeno was within two months forced to make a momentous decision when Odoacer deposed the last emperor in the west and asked for Zeno's recognition as a patrician officer of Zeno's court, intending to rule without an emperor.

Zeno granted this, and thus in theory became the first emperor of a united Roman Empire since 395. In reality, he all but wrote off the west until several years later, when Odoacer began to violate the terms of his agreement with Zeno. At the same time, Zeno sent a mission to Carthage with the intent of making a permanent peace settlement with Geiseric, who was still making constant raids on eastern cities and merchant shipping. By recognizing Geiseric as an independent king and with the full extent of his conquests, Zeno was able to hammer out a peace which ended the Vandal attacks in the east, brought freedom of religion to the Catholics under Vandal rule, and which lasted for more than 50 years. Since 472 the aggressions of the two Ostrogoth leaders Theodoric had been a constant source of danger. Though Zeno at times contrived to play them off against each other, they in turn were able to profit by his dynastic rivalries, and it was only by offering them pay and high command that he kept them from attacking Constantinople itself. Zeno survived another revolt in 478, when his mother-in-law Verina attempted to kill Illus for turning against Basiliscus, her brother. The revolt was led by her son-in-law Marcian and the Ostrogoth warlord Theoderic Strabo, but Illus again proved his loyalty to Zeno by quashing the revolt. However, Illus and Zeno had a falling out by 484, and once again Zeno had to put down a bloody revolt in the east. In 487 he induced Theodoric, son of Theodemir, to invade Italy and establish his new kingdom. After Theodoric Strabo died in 481, the future Theodoric the Great became king of the entire Ostrogothic nation and began to become a trouble in the Balkan peninsula. Zeno got rid of the problem by sending him to Italy to fight Odoacer, all but eliminating the German presence in the east. He died on April 9, 491, after ruling for 17 years and 2 months. Because he and Ariadne had no other children, his widow chose a favored member of the imperial court, Anastasius, to succeed him.

August 476 – 9 April 491)

Zeno's original name was Tarasis, and more accurately Tarasikodissa in his native Isaurian language. Tarasis was born in Isauria, at Rusumblada, later renamed Zenonopolis in Zeno's honour. His father was called Kodisa (as attested by his patronimic "Tarasicodissa"), his mother Lallis, his brother Longinus. Tarasis had a wife, Arcadia, whose name indicates a relationship with the Constantinopolitan aristocracy, and whose statue was erected near the Baths of Arcadius, along the steps that led to Topoi. The emperor Leo called him to Constantinople as the leader of a force of Isaurians in order to counter the ever-growing German influence over the empire. Also a special imperial guard was set up, made up entirely of Isaurians, and Zeno was granted command of this highly important force. In 466, he exposed the treachery of Ardabur, the son of the Alans eastern magister militum Aspar and made himself even more indispensable. By 468, when Leo's incompetent generals led the Byzantine fleet to disaster in a campaign against the Vandals, was considered Leo's best general. It was only at that stage that he assumed the name Zeno. Apparently it was the name of a dignitary of high standing back in Isauria, and Zeno thought it more befitting of his new high office to have a name less common than Tarasicodissa. To further increase the bond with his new Isaurian guardsmen, Leo married his elder daughter Aelia Ariadne to Zeno. Although designed by Leo to secure the Isaurian support against the aforementioned ambitious minister Aspar, this political arrangement brought them a son, who was a boy to became the emperor Leo II upon the death of his grandfather in 473. In AD 467-8 Zeno was given the powerful position of 'Master of Soldiers' in Thrace to repel an assault by the Huns under the son of Attila, Denzig. While on a campaign in Thrace he narrowly escaped assassination instigated by Aspar. On Tarasicodissa's return to the capital, Aspar was killed on Leo's orders and Tarasicodissa became magister militum in his own right. Next, in AD 473 Zeno was made 'Master of Soldiers' of the eastern empire, taking Aspar's place. In October AD 473 Leo elevated his five year-old grandson, who was the son of Zeno and Aelia Ariadne, to be co-emperor Leo II. When Leo became ill and died on November 17, Zeno became sole emperor. He continued to be unpopular with the people and senate because of his "foreign" origins. A revolt fomented by Verina in favour of her brother Basiliscus in January of 475 and the antipathy to his Isaurian soldiers and administrators in Constantinople forced him to flee the capital for the city of Antioch. Zeno was compelled to shut himself up in a fortress and spent the next 20 months raising an army, largely made up of fellow Isaurians, and marched on Constantinople in August 476. The growing misgovernment and unpopularity of Basiliscus ultimately enabled Zeno to re-enter Constantinople unopposed in 476 after an army led by the general Illus defected to Zeno. His rival was banished to Phrygia, where he soon afterwards died. Restored to rule of the entire empire, Zeno was within two months forced to make a momentous decision when Odoacer deposed the last emperor in the west and asked for Zeno's recognition as a patrician officer of Zeno's court, intending to rule without an emperor.

Zeno granted this, and thus in theory became the first emperor of a united Roman Empire since 395. In reality, he all but wrote off the west until several years later, when Odoacer began to violate the terms of his agreement with Zeno. At the same time, Zeno sent a mission to Carthage with the intent of making a permanent peace settlement with Geiseric, who was still making constant raids on eastern cities and merchant shipping. By recognizing Geiseric as an independent king and with the full extent of his conquests, Zeno was able to hammer out a peace which ended the Vandal attacks in the east, brought freedom of religion to the Catholics under Vandal rule, and which lasted for more than 50 years. Since 472 the aggressions of the two Ostrogoth leaders Theodoric had been a constant source of danger. Though Zeno at times contrived to play them off against each other, they in turn were able to profit by his dynastic rivalries, and it was only by offering them pay and high command that he kept them from attacking Constantinople itself. Zeno survived another revolt in 478, when his mother-in-law Verina attempted to kill Illus for turning against Basiliscus, her brother. The revolt was led by her son-in-law Marcian and the Ostrogoth warlord Theoderic Strabo, but Illus again proved his loyalty to Zeno by quashing the revolt. However, Illus and Zeno had a falling out by 484, and once again Zeno had to put down a bloody revolt in the east. In 487 he induced Theodoric, son of Theodemir, to invade Italy and establish his new kingdom. After Theodoric Strabo died in 481, the future Theodoric the Great became king of the entire Ostrogothic nation and began to become a trouble in the Balkan peninsula. Zeno got rid of the problem by sending him to Italy to fight Odoacer, all but eliminating the German presence in the east. He died on April 9, 491, after ruling for 17 years and 2 months. Because he and Ariadne had no other children, his widow chose a favored member of the imperial court, Anastasius, to succeed him.

I Like The Holocaust- Centurion

- Posts : 237

Join date : 2017-07-09

Re: The Byzantine Emperors

Re: The Byzantine Emperors

Anastasius I Dicorus (431 – 518) Reigned ( 491 – 518)

Anastasius was born at Dyrrachium 431. He was born into an Illyrian family, the son of Pompeius, nobleman of Dyrrachium, and wife Anastasia Constantina. His mother was an Arian, sister of Clearchus, also an Arian, and a paternal granddaughter of Gallus, son of Anastasia and husband, in turn daughter of Flavius Claudius Constantius Gallus and wife and cousin Constantina. Before becoming emperor, Anastasius was a particularly successful administrator in the department of finance.

After Zeno's death, his brother Longinus had hoped to become Emperor. Anastasius exiled him to the Thebaid in Egypt and expelled other Isaurians from Constantinople. Other non-Isaurian officials were also removed. These actions provoked an Isaurian revolt. Although the main rebel army, led by Longinus of Cardala, was rapidly defeated in 491 at Cotyaeum in Phrygia, it was not until 498 that all the rebels were mopped up from their Isaurian strongholds. In the Balkans, Bulgar raids across the Danube from as early as 493 prompted construction of the Long Walls between the Propontis and the Black Sea, as well as renewed work on Danubian defenses. These defensive efforts had been made possible once Theoderic's Goths had left the Balkans for Italy. Anastasius also faced minor problems along the eastern frontier in the first decade of his reign. The long-awaited war with Persia broke out in 502. Despite early setbacks, the Romans finally prevailed and peace was made in 506, followed by intense work on eastern defenses, especially at Dara. Anastasius recognized Theoderic as king in Italy in 497, though conflict briefly ensued over Pannonia in 505-510, before peace was made. Anastasius' religious beliefs were strongly Monophysite, though at his accession he had made professions of Chalcedonianism. The increasing displays of Monophysitism led to tension with the strongly Chalcedonian Patriarch of Constantinople, Euphemius. Anastasius exiled Euphemius in 496 and replaced him as patriarch with the Chalcedonian Macedonius. In 511 Anastasius replaced Macedonius with a Monophysite patriarch and in Antioch in 512 appointed the Monophysite Severus as patriarch there. The replacement of Macedonius in 511 provoked riots in Constantinople and the revolt of Vitalian in Thrace. Vitalian was the magister militum per Thracias who used his army in an attempt to force Chalcedonian orthodoxy on Anastasius, not to replace him. Anastasius was prepared to discuss Chalcedon with Pope Hormisdas, but Hormisdas' attitude to Acacius, the patriarch of Constantinople who had been excommunicated in Zeno's reign, and his insistence that the emperor and eastern bishops approve Chalcedon without qualification sabotaged negotiations. Vitalian was defeated in Thrace in 515 and went into hiding. Attempts to replace the Patriarch of Jerusalem with a Monophysite in 516 provoked riots and Anastasius did not force the issue. Anastasius, with the assistance of the Praetorian Prefect, Marinus, reformed finances by abolishing the chrysargyron. In 494 he reformed the coinage, issuing a much wider range of bronze coins, which had previously been in short supply. In 498 the collatio lustralis, a tax on craftsmen, was also abolished, while successful efforts were made to increase the efficiency of tax collection and even to reduce the rates of land taxation. At his death he was able to leave a large surplus of 320,000 lbs. gold. . He died 8/10 July, 518 and was succeeded by Justin. He was buried with Ariadne in the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople.

Anastasius was born at Dyrrachium 431. He was born into an Illyrian family, the son of Pompeius, nobleman of Dyrrachium, and wife Anastasia Constantina. His mother was an Arian, sister of Clearchus, also an Arian, and a paternal granddaughter of Gallus, son of Anastasia and husband, in turn daughter of Flavius Claudius Constantius Gallus and wife and cousin Constantina. Before becoming emperor, Anastasius was a particularly successful administrator in the department of finance.

After Zeno's death, his brother Longinus had hoped to become Emperor. Anastasius exiled him to the Thebaid in Egypt and expelled other Isaurians from Constantinople. Other non-Isaurian officials were also removed. These actions provoked an Isaurian revolt. Although the main rebel army, led by Longinus of Cardala, was rapidly defeated in 491 at Cotyaeum in Phrygia, it was not until 498 that all the rebels were mopped up from their Isaurian strongholds. In the Balkans, Bulgar raids across the Danube from as early as 493 prompted construction of the Long Walls between the Propontis and the Black Sea, as well as renewed work on Danubian defenses. These defensive efforts had been made possible once Theoderic's Goths had left the Balkans for Italy. Anastasius also faced minor problems along the eastern frontier in the first decade of his reign. The long-awaited war with Persia broke out in 502. Despite early setbacks, the Romans finally prevailed and peace was made in 506, followed by intense work on eastern defenses, especially at Dara. Anastasius recognized Theoderic as king in Italy in 497, though conflict briefly ensued over Pannonia in 505-510, before peace was made. Anastasius' religious beliefs were strongly Monophysite, though at his accession he had made professions of Chalcedonianism. The increasing displays of Monophysitism led to tension with the strongly Chalcedonian Patriarch of Constantinople, Euphemius. Anastasius exiled Euphemius in 496 and replaced him as patriarch with the Chalcedonian Macedonius. In 511 Anastasius replaced Macedonius with a Monophysite patriarch and in Antioch in 512 appointed the Monophysite Severus as patriarch there. The replacement of Macedonius in 511 provoked riots in Constantinople and the revolt of Vitalian in Thrace. Vitalian was the magister militum per Thracias who used his army in an attempt to force Chalcedonian orthodoxy on Anastasius, not to replace him. Anastasius was prepared to discuss Chalcedon with Pope Hormisdas, but Hormisdas' attitude to Acacius, the patriarch of Constantinople who had been excommunicated in Zeno's reign, and his insistence that the emperor and eastern bishops approve Chalcedon without qualification sabotaged negotiations. Vitalian was defeated in Thrace in 515 and went into hiding. Attempts to replace the Patriarch of Jerusalem with a Monophysite in 516 provoked riots and Anastasius did not force the issue. Anastasius, with the assistance of the Praetorian Prefect, Marinus, reformed finances by abolishing the chrysargyron. In 494 he reformed the coinage, issuing a much wider range of bronze coins, which had previously been in short supply. In 498 the collatio lustralis, a tax on craftsmen, was also abolished, while successful efforts were made to increase the efficiency of tax collection and even to reduce the rates of land taxation. At his death he was able to leave a large surplus of 320,000 lbs. gold. . He died 8/10 July, 518 and was succeeded by Justin. He was buried with Ariadne in the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople.

I Like The Holocaust- Centurion

- Posts : 237

Join date : 2017-07-09

Re: The Byzantine Emperors

Re: The Byzantine Emperors

Justin I (450 – 527) Reigned (518 – 527)

Justin was born in the province of Dardania belonging to the diocese of Dacia, which along with Macedonia made up the prefecture of Illyricum. It was an area which had suffered severely from barbarian attacks: in 447 a devastating raid of the Huns, which reached as far south as Thermopylae, left a wake of destruction through Illyricum and forced the praetorian prefect to flee from Sirmium to Thessaloniki. Then it was the turn of the Ostrogoths who ravaged the land until the emperor Leo I made peace in 461. It must have been about this time that Justin and two companions with Thracian names, Zimarchus and Dityvistus, all of them young men with good physiques, set out for Constantinople with only the clothes they had on their backs and a little bread in their pockets, trying to escape the grinding poverty of their homeland. The emperor Leo was organizing a new corps of palace guards, the excubitors, 300 in number, who were intended to counterbalance German predominance at court. These three young Thracians were enrolled.[[2]] We hear no more of Justin's companions, but Justin himself was evidently a competent soldier who rose through the ranks, and in 518, when the emperor Anastasius died, he was commander of the excubitors, the only effective troops on the scene. The death took place on the night of 8 July, and the silentarii (gentlemen ushers at court) immediately summoned the master of offices, Celer, and Justin. Celer commanded the scholarians, but they were ornamental soldiers; Justin, whose palace guard could fight if necessary, was in a pivotal position. In the morning of 9 July, the people assembled in the Hippodrome, and the high officials, including the patriarch, met in the Great Palace to choose a successor. Anastasius had no immediate heir though he had nephews, one of whom, Hypatius, an experienced soldier of mediocre accomplishment, might have been an obvious candidate for the throne. But he held the office of master of soldiers in the east and was probably in Antioch when his uncle died. Justin was not considered at first. We may be certain that his nephew Justinian, a lowly candidatus at the time, was not considered at all, although a later tradition claimed that some put him forward. But the people in the Hippodrome grew impatient, and the high officials, becoming a little panicky, eventually put forward Justin. He was taken to the imperial loge in the Hippodrome and invested there with the imperial robes. The donative he offered the troops on his inauguration was exactly the same as that offered by Leo I in 457 and Anastasius I in 491: 5 nomismata and one pound of silver to each soldier. On 1 August, Justin wrote to Pope Hormisdas in Rome, announcing his elevation and saying that he had been chosen against his will. In fact, John Malalas preserves a tradition that Justin was more willing than he claimed. The chamberlain Amantius had a candidate of his own for the throne, Theocritus, the count of his Domestics, and he gave Justin money with which he was to buy support. But Justin used the money to purchase support for himself. On the ninth day after his acclamation, he put Amantius and Theocritus to death. Justin broke sharply with the Monophysitism of his predecessor, Anastasius. Vitalian, the champion of the Chalcedonians, who was still lurking in the Dobrudja after his defeat by the imperial army, was recalled. Until his murder in July, 520, he overshadowed the emperor's nephew, Justinian. Justinian was given the rank of patrician on his uncle's accession and appointed Count of the Domestics, but Vitalian was consul for 520; Justinian's first consulship took place the year following. In the east, the Monophysites suffered a vigorous persecution which is well documented by John of Ephesus, who was born in Amida (modern Diyarbakir in Turkey) and knew the Monophysite monasteries and holy men in Syria at first hand. Severus, the patriarch of Antioch and the leading theologian of the Monophysites, escaped to Egypt where the patriarch of Alexandria Timothy III gave him refuge. Monophysitism had become almost a national religion in Egypt since the Council of Chalcedon in 451, and Justin never extended his persecution there. Elsewhere the new regime moved swiftly to restore orthodoxy as defined by the Creed of Chalcedon. On 20 July, 518, a synod was held in Constantinople of the bishops in the region. It pronounced anathema against Severus of Antioch, and the patriarch John of Constantinople sent letters to all bishops of importance with copies of the synodal decrees. Upon receipt of his letter, the patriarch John of Jerusalem summoned a synod, attended by Mar Saba, the archimandrite of the lauras in Palestine and a strong Chalcedonian, which followed the examples of Constantinople. In the province of Syria Secunda, a synod was also held which excommunicated Severus of Antioch who narrowly escaped arrest. Letters were dispatched from Constantinople to Pope Hormisdas: one from Justin, another, more peremptory in tone, from Justinian, and a third from the patriarch. The letters took more than three months to reach Rome and Hormisdas' reply was not returned until the new year. The pope declined the invitation to come to Constantinople in person, but he sent a delegation to set forth Rome's non-negotiable position. The papal legates were forbidden to discuss the issues, but they took with them as interpreter and observer a deacon named Dioscorus, a Greek from Alexandria. When it was necessary to explain the guilt of Acacius, the patriarch of Alexandria who was author of the Henotikon which had led to the so-called 'Acacian schism' in the reign of Zeno, Dioscorus, who was not an official legate, was free to speak and put forth the papal position that Hormisdas suggested that Justin make him patriarch of Alexandria: advice which Justin ignored. The pope demanded surrender: the condemnation of Acacius, his heretical successors on the patriarchal throne, all prelates who had remained in communion with them, and the emperors Zeno and Anastasius as well. The patriarch John of Constantinople was unhappy, but under pressure he signed the papal libellus on Maundy Thursday (28 March, 519) in the presence of Justin, the senate and clergy. The pope had gone too far. Excommunicating the prelates who had remained in communion with Acacius and his successors meant the excommunication of all the bishops in the east after 484 when the emperor Zeno's Henotikon was issued. The first sign of resistance came from Thessaloniki where the bishop refused to sign the papal libellus. Justin was soon aware of grassroots dissatisfaction elsewhere, and he became more flexible. Justin was a stout defender of the creed of Chalcedon but we may suppose that his years as an army officer had taught him the advantages of a reasonable approach. At the beginning of the year 519, a delegation of monks arrived in the capital from Scythia Minor (Dobrudja) with a new solution. They won Vitalian's support, for Vitalian himself came from that province and one of the delegation was a relative of his. What the monks prescribed was the formula stating that 'one of the Holy Trinity had suffered in the flesh'. It was a nearly identical formula, added to the Trisagion in the liturgy of Hagia Sophia, which had nearly cost the emperor Anastasius his throne in 512. When the Scythian monks proposed it, they were denounced immediately by the 'Sleepless Monks', the watchdogs of Chalcedonianism who were eventually to become more orthodox than the pope and were excommunicated. However, repackaged by the Scythian monks, the formula became known as the 'Theopaschite doctrine' and it interested Justinian. He sent the monks off to Rome where they tried to propagate their doctrine, but Hormisdas was unmoved and eventually sent them packing. Yet his victory of 519 solved nothing; if anything it proved the futility of Rome's policy of intransigence in the face of the Monophysite problem. When Hormisdas died in 523, his son Silverius who was eventually to become a pope himself, wrote his epitaph, one line of which reads, "Greece, vanquished by pious power, has yielded to you." The Monophysite persecution in the east continued until 520, when Vitalian was assassinated. Orthodoxy extended even to the army: soldiers were ordered to subscribe to the creed of Chalcedon or be deprived of their rations. After 520, Justin followed a more tolerant policy until the end of his life, when he was old and ill and no longer in control. In the last four months of his reign, when Justinian was co-emperor, imperial policy reverted to coercion. Yet, if Justin's application of the regulations against heresy was pragmatic, his devotion to orthodoxy remained the same. There is some irony to the fact that Pope Hormisdas' successor John did visit Constantinople to solicit for tolerance of heresy: Theodoric the Ostrogoth, who ruled Italy with a firm hand, was disquieted at the anti-heretical policies of the new regime in Constantinople and dispatched John to plead on behalf of Arianism, which was the faith of the Ostrogoths. Justin gave the pope a warm welcome, so warm that it roused Theodoric's suspicions. But the pope's efforts on behalf of the persecuted Arians had little result. When he arrived back in Ravenna, Theodoric made his disappointment clear. Theodoric's coldness may have contributed to the pope's death soon afterwards. The accession of an orthodox emperor anxious to repair relations with the papacy must have roused some disquiet in the Ostrogothic court. With the old emperor Anastasius Ostrogothic Italy had an amicable arrangement which had been regularized in 497: Italy was still part of the empire, and Theodoric ruled the Romans as the emperor's deputy and the Ostrogoths as their hereditary king. Greek distinguished between emperors and kings such as Theodoric: for the latter the title was rex, borrowed from the Latin, whereas for the former the title was . As long as the emperor in Constantinople was Monophysite, religious schism drove a wedge between him and his Roman subjects, who were firm Chalcedonians. But once the emperor was Chalcedonian and the Acacian schism was healed, the situation changed. The Romans returned to their old allegiance and Theodoric grew suspicious of their loyalty. The Ostrogoths lived in Italy as an immigrant ruling class, maintained by property appropriated from the Roman landowners - one-third of their estates, it is reported - but separated from the Romans by their religion, for the Goths were Arians, and worshipped in separate Arian churches. The situation was unstable and Theodoric was aware of it, all the more so since he had no able son to succeed him. Theodoric was anxious for good relations with the new emperor, and Justin responded positively. In 519, Justin nominated Theodoric's son-in-law Eutharic as consul to serve as Justin's colleague. Eutharic who had married Theodoric's daughter Amalasuintha, was an uncouth man who disliked Catholics, but Justin made him the first Goth to become a consul and adopted him according to Gothic customs, thereby recognizing him as Theodoric's heir. But in 522, Eutharic died, leaving a young son Athalaric, born in 518. Meanwhile Justin's anti-heretical policies bore more heavily against Arianism. After 523, Arians in the east suffered active persecution. In 524, Theodoric executed his Master of Offices, Boethius who was suspected of treasonable correspondence with the imperial court in Constantinople. While in prison he wrote the book which was the favorite of the Latin Middle Ages, the Consolation of Philosophy. There can be no doubt that Boethius was a Christian, but the Consolation could have been written by a pagan: the "Philosophia" who comforts Boethius owes more to Neoplatonism than she does to Christianity. Some scholars have suggested that in his final months, Boethius turned to the solace offered by the older religion, but the truth is probably that Boethius never recognized the antithesis between pagan philosophy and Christian theology which modern academics do. Yet we should not imagine that his attitude was shared by many: Boethius belonged to an educated upper crust which had become very thin indeed. In 525 the severe measures taken against the Arians in the east became known in Italy. Theodoric dispatched Pope John to Constantinople to remonstrate and report Theodoric's threat to persecute Italian Catholics in reprisal. John was received cordially. While in Constantinople, he performed a coronation ceremony for Justin, thereby making clear his recognition of Justin as his sovereign. But his actions fueled Theodoric's paranoia and John got a cold reception when he returned to Ravenna. He died soon after (May 18, 526). His successor, Felix IV, chosen after two months of contention, was a prelate who met Theodoric's approval. Shortly afterwards, on 30 August, Theodoric himself died, leaving the boy Athalaric as his heir. Theodoric's relations with Constantinople were not the only ones to turn sour in his last years. He had built up a network of marriage alliances in the western Mediterranean: his own second wife was a Frankish princess, a daughter had married a Burgundian prince, another had married Alaric II, the king of Visigothic Spain, and in 500 he had given his sister Amalfrida as his wife to the Vandal king Trasamund. Relations between these two Arian kingdoms were close as long as Trasamund was alive, but his successor Hilderic favored the Catholics. Trasamund's widow Amalfrida protested, and Hilderic retorted by throwing her into prison and killing her Gothic entourage. When he died, Theodoric was planning an attack on Africa that would have further clouded relations with Constantinople, which looked on Hilderic as a friend of orhodoxy. At the eastern end of the Black Sea, Lazica, the ancient Colchis between the Rioni and Chorokhi rivers was a bone of contention between the Roman empire and Persia. Persia regarded it as a satellite and yet it was Christian in religion. In 522, Tzath, the Lazic king broke with the custom of going to Persia for coronation and instead went to Constantinople, where he asked Justin to proclaim him king and baptize him. Childhood baptism, it should be remembered, was not yet universally practised: emperors in earlier centuries such as Constantine I and his son Constantius II waited until just before their deaths before being baptized. Thus Tzath, though a Christian, had probably not yet been baptized and his trip to Constantinople to receive the rite conveyed a message to Persia. Justin welcomed Tzath cordially and found him a Roman lady for his wife. The king of Persia Kawad was incensed but for the moment could not take direct action. However he got in touch with the Sabiric Huns in the northern Caucasus and negotiated an alliance with their king Zilgibi to attack the empire. But Zilbigi was too clever; he negotiated with both sides. Justin made a point of disclosing Zilgibi's treachery to Kawad. It was, he pretended, a friendly gesture: a word to the wise. Kawad confronted Zilbigi with his perfidy and when Zilbigi admitted it, Kawad slew him and most of the 20,000 Huns in the force he had brought with him. Impressed, it seems, with Justin's transparency, Kawad sought his help in a domestic problem. He had four sons and ordinarily the eldest should have succeeded him. But Kawad did not want him, probably because he had favored the Mazdakites, followers of a religious leader Mazdak who had tried to impose a radical social system on Persia; Kawad earlier in his reign had suppressed them by force. Kawad's second son had lost an eye which made him ineligible, but the Persian nobles admired his military ability and some favored him, his physical disability notwithstanding. Kawad wanted his third (or fourth?) son Khusro to succeed him and to secure the succession, he asked Justin to adopt him. Justin was willing, but it was pointed out to him by an advisor that if Khusro were adopted according to Roman law, it would give him a claim to the imperial throne. Thus Justin offered adoption according to barbarian custom: the same adoption which he had accorded Theodoric's son-in-law. The Persians found the proposal insupportable. It should also be added that negotiations to settle the differences between Persia and the empire did not go well. The opportunity for peace was lost. Kawad then moved against Iberia, modern Georgia, a Christian kingdom on the borders of the Sassanid empire: he demanded that they adopt the rites of Zororastrianism, the religion of Persia. Justin retorted by sending Probus, a nephew of the old emperor Anastasius to Bosporus (classical Panticapaeum) in the Crimea to bribe the Huns, who controlled Bosporus at that time, to help the Iberians. But the Huns were too occupied by their own internal problems to assist. Justin did, however, send a small force of Hun troops under a Byzantine officer to defend the Iberian king, Gurgenes, but the force was too weak, and the Iberian royal family was forced to flee. Iberia lost its independence and Justin lost prestige. In 526, the empire opened hostilities by launching two unsuccessful raids into Persarmenia, the part of Armenia under Persian control. By this time Justin was feeble with age and the pain of an old wound: the author of this move was certainly his nephew Justinian. The young officers leading the expeditions were members of Justinian's entourage, Sittas and Belisarius. At the same time an army was dispatched into Mesopotamia near Nisibis which probed the frontier and then pulled back, achieving nothing. It may be that Justinian thought the time was ripe to take the measure of Persia. But Justin was not the author of this change in policy, if that is what it was. Himyar, modern Yemen was an area where Christianity, Judaism and paganism competed for religious allegiance and where Ethiopia, Persia and the eastern Roman Empire competed for political advantage. In October of 523, the Christians were massacred in Najran, the center of Christianity in south Arabia. The author of the massacre was a Jew (or Jewish convert) Dhu Nuwas who had seized power in Himyar, and undertook a campaign against Christianity there. The events were to give birth to a rich martyr literature; Vasiliev notes that a thousand years later, a sixteenth-century Russian source, the Stepennaya Kniga relates the story of Najran's capture by "Dunas the Zhidovin (Jew)" and compares "Dunas" to the Tartar khan Takhtamysh who captured Moscow by cunning. The multiplicity of traditions make it difficult to discern what actually happened, and the cast of characters have names that vary: Dhu Nuwas is also known as Masruq, and the king of Abyssinia whose name in Ethiopic was Ela Atzheba is known as Elesboas (in Malalas), Hellesthaeus (in Procopius) and sometimes as Kaleb which may have been his Christian name. It appears that a Christian from Najran escaped and brought news of the massacre to Ela Atzheba along with a half-burnt copy of the Gospel. Ela Atzheba had troops with which to intervene but no ship transports; he got in touch with Justin through the patriarch of Alexandria, Timothy III. It should be noted that both Ela Atzheba and Timothy were Monophysite Christians whereas Justin was a devout Chalcedonian, but where the interests of Christianity outside the borders of the empire were concerned, theological differences did not matter. Justin mustered transport ships for the Ethiopian army. In two campaigns Ela Atzheba took the Himyarite capital, killed Dhu Nuwas and set up a Christian king as an Ethiopian client. One tradition had it that Dhu Nuwas, facing defeat, rode his horse into the sea and was never seen again. The situation in Yemen, however, remained volatile and in 570-72, after Justinian's death, Persia succeeded in occupying it. The society of sixth-century Byzantium was a fluid one, but by every standard of the time, Theodora was an unsuitable consort for Justin's nephew, Justinian. Justin's other nephew Germanus made a "society" marriage into the noble family of the Anicii, a Roman family which had moved to Constantinople, but Justinian's marriage was quite the reverse. Theodora had a background in popular theatre, which specialized in pornographic mimes. This was, in fact, the only type of theatre which allowed women on stage. Actresses were on the level of prostitutes, denied the rites of the church except after a deathbed repentance. Theodora had left the stage, however, by the time Justinian met her. She had become a devout Christian during a stay in Alexandria: there is a tradition that she met and received much kindness from the patriarch, Timothy III. However her creed was Monophysite which cannot have made her a more suitable consort for Justin's heir, Justinian. Justinian's hunger for power, mingled with a certain insecurity, was barely concealed during the early years of Justin's reign. At first, Vitalian was a competitor, but assassination had removed him in 520. Perhaps Justinian was responsible. Germanus and his brother Boraides, two other nephews whom Justin had brought to Constantinople, seem never to have been rivals. However during these early years of Justin's reign, without the knowledge of his uncle, Justinian seems to have encouraged street violence. The rivalry between the fans of the Blues and the Greens in the Hippodrome spilled out into the avenues and alleys of Constantinople. The young men who supported the Blue and Green factions affected Hunnic dress and hair-styles, and their gangs made life dangerous for the solid citizens of the capital. Justinian was a strong supporter of the Blues, as was Theodora. Procopius accuses Justinian of instigating the street violence and although his Anekdota is not a completely reliable witness where Justinian is concerned, it was true that aficionados of the Blues who committed outrages could count on Justinian's support to help them evade punishment. The more numerous Greens, who had no such patron, harbored a sense of injustice. It is hard to make sense out of this. At one time, scholars considered the Greens supporters of Monophysitism and the Blues supporters of Chalcedonian orthodoxy,[[16]] but the evidence for that has been effectively disputed by Alan Cameron: the general view now is that the Blue and Green fans were high-spirited youth who had few other outlets for their energy. In any case, Justinian's partisanship fueled the disorder until 524 or 525 when Justinian fell ill. During his illness Justin was informed of the dangers on the streets and the cause, which apparently had been kept from him until this time, and he ordered the urban prefect Theodotus Colocynthius (the 'Pumpkin') to restore order. Theodotus acted vigorously; some Blues were hanged or burned alive. When Justinian recovered, he took revenge on Theodotus who was deprived of his office and sent to Jerusalem, but his support for the Blues became more circumspect. About the same time, in 525, he married Theodora, no doubt in the Great Church of Hagia Sophia. There is probably no connection. But Justinian had to overcome opposition in order to wed Theodora. First, Justin's wife Euphemia would not accept Theodora although she was fond of Justinian and opposed him in nothing else as far as we know. Euphemia had been a former slave of Justin's named Lupicina, whom he had married. Once she became empress, however, she became respectable. She changed her name Lupicina for Euphemia which better fitted her altered station, and she refused to have a woman with Theodora's past as the wife of Justin's heir. The second problem was that Roman law forbade a senator to marry a woman from the theater. The first obstacle was removed by Euphemia's death in 524. Then, at Justinian's urging, Justin promulgated a law which removed all disabilities from actresses who repented of their past lives. The way was cleared for Theodora's marriage and not only for her: about the same time, the army officer Sittas married Theodora's older sister Comito who had also been a mime actress. A little later, Justinian received the rank of nobilissimus, and on 1 April, 527, Justin proclaimed Justinian co-emperor. Three days later, in Hagia Sophia, the patriarch crowned Justinian and Theodora emperor and empress. The ex-actress had come a long way. Four months later, Justin died, and the future of the empire devolved into the eager hands of Theodora and Justinian. On August 1, 527 AD Justin died in Constantinople and was succeeded by his son Justinian I.

The Byzantine Empire at the time of is death in 527.

Justin was born in the province of Dardania belonging to the diocese of Dacia, which along with Macedonia made up the prefecture of Illyricum. It was an area which had suffered severely from barbarian attacks: in 447 a devastating raid of the Huns, which reached as far south as Thermopylae, left a wake of destruction through Illyricum and forced the praetorian prefect to flee from Sirmium to Thessaloniki. Then it was the turn of the Ostrogoths who ravaged the land until the emperor Leo I made peace in 461. It must have been about this time that Justin and two companions with Thracian names, Zimarchus and Dityvistus, all of them young men with good physiques, set out for Constantinople with only the clothes they had on their backs and a little bread in their pockets, trying to escape the grinding poverty of their homeland. The emperor Leo was organizing a new corps of palace guards, the excubitors, 300 in number, who were intended to counterbalance German predominance at court. These three young Thracians were enrolled.[[2]] We hear no more of Justin's companions, but Justin himself was evidently a competent soldier who rose through the ranks, and in 518, when the emperor Anastasius died, he was commander of the excubitors, the only effective troops on the scene. The death took place on the night of 8 July, and the silentarii (gentlemen ushers at court) immediately summoned the master of offices, Celer, and Justin. Celer commanded the scholarians, but they were ornamental soldiers; Justin, whose palace guard could fight if necessary, was in a pivotal position. In the morning of 9 July, the people assembled in the Hippodrome, and the high officials, including the patriarch, met in the Great Palace to choose a successor. Anastasius had no immediate heir though he had nephews, one of whom, Hypatius, an experienced soldier of mediocre accomplishment, might have been an obvious candidate for the throne. But he held the office of master of soldiers in the east and was probably in Antioch when his uncle died. Justin was not considered at first. We may be certain that his nephew Justinian, a lowly candidatus at the time, was not considered at all, although a later tradition claimed that some put him forward. But the people in the Hippodrome grew impatient, and the high officials, becoming a little panicky, eventually put forward Justin. He was taken to the imperial loge in the Hippodrome and invested there with the imperial robes. The donative he offered the troops on his inauguration was exactly the same as that offered by Leo I in 457 and Anastasius I in 491: 5 nomismata and one pound of silver to each soldier. On 1 August, Justin wrote to Pope Hormisdas in Rome, announcing his elevation and saying that he had been chosen against his will. In fact, John Malalas preserves a tradition that Justin was more willing than he claimed. The chamberlain Amantius had a candidate of his own for the throne, Theocritus, the count of his Domestics, and he gave Justin money with which he was to buy support. But Justin used the money to purchase support for himself. On the ninth day after his acclamation, he put Amantius and Theocritus to death. Justin broke sharply with the Monophysitism of his predecessor, Anastasius. Vitalian, the champion of the Chalcedonians, who was still lurking in the Dobrudja after his defeat by the imperial army, was recalled. Until his murder in July, 520, he overshadowed the emperor's nephew, Justinian. Justinian was given the rank of patrician on his uncle's accession and appointed Count of the Domestics, but Vitalian was consul for 520; Justinian's first consulship took place the year following. In the east, the Monophysites suffered a vigorous persecution which is well documented by John of Ephesus, who was born in Amida (modern Diyarbakir in Turkey) and knew the Monophysite monasteries and holy men in Syria at first hand. Severus, the patriarch of Antioch and the leading theologian of the Monophysites, escaped to Egypt where the patriarch of Alexandria Timothy III gave him refuge. Monophysitism had become almost a national religion in Egypt since the Council of Chalcedon in 451, and Justin never extended his persecution there. Elsewhere the new regime moved swiftly to restore orthodoxy as defined by the Creed of Chalcedon. On 20 July, 518, a synod was held in Constantinople of the bishops in the region. It pronounced anathema against Severus of Antioch, and the patriarch John of Constantinople sent letters to all bishops of importance with copies of the synodal decrees. Upon receipt of his letter, the patriarch John of Jerusalem summoned a synod, attended by Mar Saba, the archimandrite of the lauras in Palestine and a strong Chalcedonian, which followed the examples of Constantinople. In the province of Syria Secunda, a synod was also held which excommunicated Severus of Antioch who narrowly escaped arrest. Letters were dispatched from Constantinople to Pope Hormisdas: one from Justin, another, more peremptory in tone, from Justinian, and a third from the patriarch. The letters took more than three months to reach Rome and Hormisdas' reply was not returned until the new year. The pope declined the invitation to come to Constantinople in person, but he sent a delegation to set forth Rome's non-negotiable position. The papal legates were forbidden to discuss the issues, but they took with them as interpreter and observer a deacon named Dioscorus, a Greek from Alexandria. When it was necessary to explain the guilt of Acacius, the patriarch of Alexandria who was author of the Henotikon which had led to the so-called 'Acacian schism' in the reign of Zeno, Dioscorus, who was not an official legate, was free to speak and put forth the papal position that Hormisdas suggested that Justin make him patriarch of Alexandria: advice which Justin ignored. The pope demanded surrender: the condemnation of Acacius, his heretical successors on the patriarchal throne, all prelates who had remained in communion with them, and the emperors Zeno and Anastasius as well. The patriarch John of Constantinople was unhappy, but under pressure he signed the papal libellus on Maundy Thursday (28 March, 519) in the presence of Justin, the senate and clergy. The pope had gone too far. Excommunicating the prelates who had remained in communion with Acacius and his successors meant the excommunication of all the bishops in the east after 484 when the emperor Zeno's Henotikon was issued. The first sign of resistance came from Thessaloniki where the bishop refused to sign the papal libellus. Justin was soon aware of grassroots dissatisfaction elsewhere, and he became more flexible. Justin was a stout defender of the creed of Chalcedon but we may suppose that his years as an army officer had taught him the advantages of a reasonable approach. At the beginning of the year 519, a delegation of monks arrived in the capital from Scythia Minor (Dobrudja) with a new solution. They won Vitalian's support, for Vitalian himself came from that province and one of the delegation was a relative of his. What the monks prescribed was the formula stating that 'one of the Holy Trinity had suffered in the flesh'. It was a nearly identical formula, added to the Trisagion in the liturgy of Hagia Sophia, which had nearly cost the emperor Anastasius his throne in 512. When the Scythian monks proposed it, they were denounced immediately by the 'Sleepless Monks', the watchdogs of Chalcedonianism who were eventually to become more orthodox than the pope and were excommunicated. However, repackaged by the Scythian monks, the formula became known as the 'Theopaschite doctrine' and it interested Justinian. He sent the monks off to Rome where they tried to propagate their doctrine, but Hormisdas was unmoved and eventually sent them packing. Yet his victory of 519 solved nothing; if anything it proved the futility of Rome's policy of intransigence in the face of the Monophysite problem. When Hormisdas died in 523, his son Silverius who was eventually to become a pope himself, wrote his epitaph, one line of which reads, "Greece, vanquished by pious power, has yielded to you." The Monophysite persecution in the east continued until 520, when Vitalian was assassinated. Orthodoxy extended even to the army: soldiers were ordered to subscribe to the creed of Chalcedon or be deprived of their rations. After 520, Justin followed a more tolerant policy until the end of his life, when he was old and ill and no longer in control. In the last four months of his reign, when Justinian was co-emperor, imperial policy reverted to coercion. Yet, if Justin's application of the regulations against heresy was pragmatic, his devotion to orthodoxy remained the same. There is some irony to the fact that Pope Hormisdas' successor John did visit Constantinople to solicit for tolerance of heresy: Theodoric the Ostrogoth, who ruled Italy with a firm hand, was disquieted at the anti-heretical policies of the new regime in Constantinople and dispatched John to plead on behalf of Arianism, which was the faith of the Ostrogoths. Justin gave the pope a warm welcome, so warm that it roused Theodoric's suspicions. But the pope's efforts on behalf of the persecuted Arians had little result. When he arrived back in Ravenna, Theodoric made his disappointment clear. Theodoric's coldness may have contributed to the pope's death soon afterwards. The accession of an orthodox emperor anxious to repair relations with the papacy must have roused some disquiet in the Ostrogothic court. With the old emperor Anastasius Ostrogothic Italy had an amicable arrangement which had been regularized in 497: Italy was still part of the empire, and Theodoric ruled the Romans as the emperor's deputy and the Ostrogoths as their hereditary king. Greek distinguished between emperors and kings such as Theodoric: for the latter the title was rex, borrowed from the Latin, whereas for the former the title was . As long as the emperor in Constantinople was Monophysite, religious schism drove a wedge between him and his Roman subjects, who were firm Chalcedonians. But once the emperor was Chalcedonian and the Acacian schism was healed, the situation changed. The Romans returned to their old allegiance and Theodoric grew suspicious of their loyalty. The Ostrogoths lived in Italy as an immigrant ruling class, maintained by property appropriated from the Roman landowners - one-third of their estates, it is reported - but separated from the Romans by their religion, for the Goths were Arians, and worshipped in separate Arian churches. The situation was unstable and Theodoric was aware of it, all the more so since he had no able son to succeed him. Theodoric was anxious for good relations with the new emperor, and Justin responded positively. In 519, Justin nominated Theodoric's son-in-law Eutharic as consul to serve as Justin's colleague. Eutharic who had married Theodoric's daughter Amalasuintha, was an uncouth man who disliked Catholics, but Justin made him the first Goth to become a consul and adopted him according to Gothic customs, thereby recognizing him as Theodoric's heir. But in 522, Eutharic died, leaving a young son Athalaric, born in 518. Meanwhile Justin's anti-heretical policies bore more heavily against Arianism. After 523, Arians in the east suffered active persecution. In 524, Theodoric executed his Master of Offices, Boethius who was suspected of treasonable correspondence with the imperial court in Constantinople. While in prison he wrote the book which was the favorite of the Latin Middle Ages, the Consolation of Philosophy. There can be no doubt that Boethius was a Christian, but the Consolation could have been written by a pagan: the "Philosophia" who comforts Boethius owes more to Neoplatonism than she does to Christianity. Some scholars have suggested that in his final months, Boethius turned to the solace offered by the older religion, but the truth is probably that Boethius never recognized the antithesis between pagan philosophy and Christian theology which modern academics do. Yet we should not imagine that his attitude was shared by many: Boethius belonged to an educated upper crust which had become very thin indeed. In 525 the severe measures taken against the Arians in the east became known in Italy. Theodoric dispatched Pope John to Constantinople to remonstrate and report Theodoric's threat to persecute Italian Catholics in reprisal. John was received cordially. While in Constantinople, he performed a coronation ceremony for Justin, thereby making clear his recognition of Justin as his sovereign. But his actions fueled Theodoric's paranoia and John got a cold reception when he returned to Ravenna. He died soon after (May 18, 526). His successor, Felix IV, chosen after two months of contention, was a prelate who met Theodoric's approval. Shortly afterwards, on 30 August, Theodoric himself died, leaving the boy Athalaric as his heir. Theodoric's relations with Constantinople were not the only ones to turn sour in his last years. He had built up a network of marriage alliances in the western Mediterranean: his own second wife was a Frankish princess, a daughter had married a Burgundian prince, another had married Alaric II, the king of Visigothic Spain, and in 500 he had given his sister Amalfrida as his wife to the Vandal king Trasamund. Relations between these two Arian kingdoms were close as long as Trasamund was alive, but his successor Hilderic favored the Catholics. Trasamund's widow Amalfrida protested, and Hilderic retorted by throwing her into prison and killing her Gothic entourage. When he died, Theodoric was planning an attack on Africa that would have further clouded relations with Constantinople, which looked on Hilderic as a friend of orhodoxy. At the eastern end of the Black Sea, Lazica, the ancient Colchis between the Rioni and Chorokhi rivers was a bone of contention between the Roman empire and Persia. Persia regarded it as a satellite and yet it was Christian in religion. In 522, Tzath, the Lazic king broke with the custom of going to Persia for coronation and instead went to Constantinople, where he asked Justin to proclaim him king and baptize him. Childhood baptism, it should be remembered, was not yet universally practised: emperors in earlier centuries such as Constantine I and his son Constantius II waited until just before their deaths before being baptized. Thus Tzath, though a Christian, had probably not yet been baptized and his trip to Constantinople to receive the rite conveyed a message to Persia. Justin welcomed Tzath cordially and found him a Roman lady for his wife. The king of Persia Kawad was incensed but for the moment could not take direct action. However he got in touch with the Sabiric Huns in the northern Caucasus and negotiated an alliance with their king Zilgibi to attack the empire. But Zilbigi was too clever; he negotiated with both sides. Justin made a point of disclosing Zilgibi's treachery to Kawad. It was, he pretended, a friendly gesture: a word to the wise. Kawad confronted Zilbigi with his perfidy and when Zilbigi admitted it, Kawad slew him and most of the 20,000 Huns in the force he had brought with him. Impressed, it seems, with Justin's transparency, Kawad sought his help in a domestic problem. He had four sons and ordinarily the eldest should have succeeded him. But Kawad did not want him, probably because he had favored the Mazdakites, followers of a religious leader Mazdak who had tried to impose a radical social system on Persia; Kawad earlier in his reign had suppressed them by force. Kawad's second son had lost an eye which made him ineligible, but the Persian nobles admired his military ability and some favored him, his physical disability notwithstanding. Kawad wanted his third (or fourth?) son Khusro to succeed him and to secure the succession, he asked Justin to adopt him. Justin was willing, but it was pointed out to him by an advisor that if Khusro were adopted according to Roman law, it would give him a claim to the imperial throne. Thus Justin offered adoption according to barbarian custom: the same adoption which he had accorded Theodoric's son-in-law. The Persians found the proposal insupportable. It should also be added that negotiations to settle the differences between Persia and the empire did not go well. The opportunity for peace was lost. Kawad then moved against Iberia, modern Georgia, a Christian kingdom on the borders of the Sassanid empire: he demanded that they adopt the rites of Zororastrianism, the religion of Persia. Justin retorted by sending Probus, a nephew of the old emperor Anastasius to Bosporus (classical Panticapaeum) in the Crimea to bribe the Huns, who controlled Bosporus at that time, to help the Iberians. But the Huns were too occupied by their own internal problems to assist. Justin did, however, send a small force of Hun troops under a Byzantine officer to defend the Iberian king, Gurgenes, but the force was too weak, and the Iberian royal family was forced to flee. Iberia lost its independence and Justin lost prestige. In 526, the empire opened hostilities by launching two unsuccessful raids into Persarmenia, the part of Armenia under Persian control. By this time Justin was feeble with age and the pain of an old wound: the author of this move was certainly his nephew Justinian. The young officers leading the expeditions were members of Justinian's entourage, Sittas and Belisarius. At the same time an army was dispatched into Mesopotamia near Nisibis which probed the frontier and then pulled back, achieving nothing. It may be that Justinian thought the time was ripe to take the measure of Persia. But Justin was not the author of this change in policy, if that is what it was. Himyar, modern Yemen was an area where Christianity, Judaism and paganism competed for religious allegiance and where Ethiopia, Persia and the eastern Roman Empire competed for political advantage. In October of 523, the Christians were massacred in Najran, the center of Christianity in south Arabia. The author of the massacre was a Jew (or Jewish convert) Dhu Nuwas who had seized power in Himyar, and undertook a campaign against Christianity there. The events were to give birth to a rich martyr literature; Vasiliev notes that a thousand years later, a sixteenth-century Russian source, the Stepennaya Kniga relates the story of Najran's capture by "Dunas the Zhidovin (Jew)" and compares "Dunas" to the Tartar khan Takhtamysh who captured Moscow by cunning. The multiplicity of traditions make it difficult to discern what actually happened, and the cast of characters have names that vary: Dhu Nuwas is also known as Masruq, and the king of Abyssinia whose name in Ethiopic was Ela Atzheba is known as Elesboas (in Malalas), Hellesthaeus (in Procopius) and sometimes as Kaleb which may have been his Christian name. It appears that a Christian from Najran escaped and brought news of the massacre to Ela Atzheba along with a half-burnt copy of the Gospel. Ela Atzheba had troops with which to intervene but no ship transports; he got in touch with Justin through the patriarch of Alexandria, Timothy III. It should be noted that both Ela Atzheba and Timothy were Monophysite Christians whereas Justin was a devout Chalcedonian, but where the interests of Christianity outside the borders of the empire were concerned, theological differences did not matter. Justin mustered transport ships for the Ethiopian army. In two campaigns Ela Atzheba took the Himyarite capital, killed Dhu Nuwas and set up a Christian king as an Ethiopian client. One tradition had it that Dhu Nuwas, facing defeat, rode his horse into the sea and was never seen again. The situation in Yemen, however, remained volatile and in 570-72, after Justinian's death, Persia succeeded in occupying it. The society of sixth-century Byzantium was a fluid one, but by every standard of the time, Theodora was an unsuitable consort for Justin's nephew, Justinian. Justin's other nephew Germanus made a "society" marriage into the noble family of the Anicii, a Roman family which had moved to Constantinople, but Justinian's marriage was quite the reverse. Theodora had a background in popular theatre, which specialized in pornographic mimes. This was, in fact, the only type of theatre which allowed women on stage. Actresses were on the level of prostitutes, denied the rites of the church except after a deathbed repentance. Theodora had left the stage, however, by the time Justinian met her. She had become a devout Christian during a stay in Alexandria: there is a tradition that she met and received much kindness from the patriarch, Timothy III. However her creed was Monophysite which cannot have made her a more suitable consort for Justin's heir, Justinian. Justinian's hunger for power, mingled with a certain insecurity, was barely concealed during the early years of Justin's reign. At first, Vitalian was a competitor, but assassination had removed him in 520. Perhaps Justinian was responsible. Germanus and his brother Boraides, two other nephews whom Justin had brought to Constantinople, seem never to have been rivals. However during these early years of Justin's reign, without the knowledge of his uncle, Justinian seems to have encouraged street violence. The rivalry between the fans of the Blues and the Greens in the Hippodrome spilled out into the avenues and alleys of Constantinople. The young men who supported the Blue and Green factions affected Hunnic dress and hair-styles, and their gangs made life dangerous for the solid citizens of the capital. Justinian was a strong supporter of the Blues, as was Theodora. Procopius accuses Justinian of instigating the street violence and although his Anekdota is not a completely reliable witness where Justinian is concerned, it was true that aficionados of the Blues who committed outrages could count on Justinian's support to help them evade punishment. The more numerous Greens, who had no such patron, harbored a sense of injustice. It is hard to make sense out of this. At one time, scholars considered the Greens supporters of Monophysitism and the Blues supporters of Chalcedonian orthodoxy,[[16]] but the evidence for that has been effectively disputed by Alan Cameron: the general view now is that the Blue and Green fans were high-spirited youth who had few other outlets for their energy. In any case, Justinian's partisanship fueled the disorder until 524 or 525 when Justinian fell ill. During his illness Justin was informed of the dangers on the streets and the cause, which apparently had been kept from him until this time, and he ordered the urban prefect Theodotus Colocynthius (the 'Pumpkin') to restore order. Theodotus acted vigorously; some Blues were hanged or burned alive. When Justinian recovered, he took revenge on Theodotus who was deprived of his office and sent to Jerusalem, but his support for the Blues became more circumspect. About the same time, in 525, he married Theodora, no doubt in the Great Church of Hagia Sophia. There is probably no connection. But Justinian had to overcome opposition in order to wed Theodora. First, Justin's wife Euphemia would not accept Theodora although she was fond of Justinian and opposed him in nothing else as far as we know. Euphemia had been a former slave of Justin's named Lupicina, whom he had married. Once she became empress, however, she became respectable. She changed her name Lupicina for Euphemia which better fitted her altered station, and she refused to have a woman with Theodora's past as the wife of Justin's heir. The second problem was that Roman law forbade a senator to marry a woman from the theater. The first obstacle was removed by Euphemia's death in 524. Then, at Justinian's urging, Justin promulgated a law which removed all disabilities from actresses who repented of their past lives. The way was cleared for Theodora's marriage and not only for her: about the same time, the army officer Sittas married Theodora's older sister Comito who had also been a mime actress. A little later, Justinian received the rank of nobilissimus, and on 1 April, 527, Justin proclaimed Justinian co-emperor. Three days later, in Hagia Sophia, the patriarch crowned Justinian and Theodora emperor and empress. The ex-actress had come a long way. Four months later, Justin died, and the future of the empire devolved into the eager hands of Theodora and Justinian. On August 1, 527 AD Justin died in Constantinople and was succeeded by his son Justinian I.

The Byzantine Empire at the time of is death in 527.

I Like The Holocaust- Centurion

- Posts : 237

Join date : 2017-07-09

Re: The Byzantine Emperors

Re: The Byzantine Emperors

Justinian The Great (482 - 565) Reigned (527 - 565)

.jpg)